The Resurgence of Modern Piracy

Even at the turn of the 21st century, piracy was a formidable and frustrating obstacle for commercial ships passing through one of the many buccaneer-infested areas. For about a year, pirate raids were conducted almost every day all over the world, capturing hostages and cargo. Though it might be amusing to imagine a bandit straight from Treasure Island with a hook and an eyepatch, modern piracy was a serious problem for shipping businesses and people, and might still be today in 2017.

According to Oceans Beyond Piracy’s 2011 report on the area, the money to pay for damage resulting from pirate activity, as well as funds for preventative measures, amounted to $6.6 billion to $6.9 billion dollars just for pirates in the area of Somalia alone during its apex in 2011. Pirates injured and abused hostages, held ships captive, and raided commercial boats; all incidents evident in the lucrative cycle of pirating many thought would never end. In 2012, it seemed that piracy had all but disappeared.

However, just a few weeks ago, the E.U. reported that pirates off the coast of Somalia hijacked the first commercial boat they had for years, refueling concerns for the area. The Aris-13, an oil tanker that fell victim to the pirates, had reported a day before the attack that it was being trailed by two skiffs. The crew alarmed the emergency system, and soon afterward, they suspiciously turned the ship to arrive at the Somali port of Alula, as reported by John Steed, an advocate for Oceans Beyond Piracy, an organization who works for reducing violence at sea.

Sri Lanka announced that eight of its nationals were on board, and the European Union was sent an undisclosed ransom from the pirates. Many experts speculated that after a long period of peace in the region, relaxed boat owners established fewer precautions, leading to the capture of their boat.

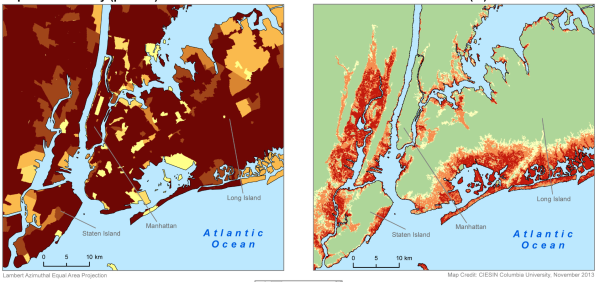

It is not surprising that the captains were relaxed in face of pirating precautions. From almost a year of intense pirate attacks in 2011, including twenty-seven hijacks in the third quarter, experts hired by the E.U. estimated there to be 3,000 to 5,000 pirates in the Somalian pirating system alone. This number is large, but imaginable, considering the infrastructure of investors from the Somalian mainland as well as from other places funneling capital in lucrative pirating activities.

However, in 2012, the European Union Naval Force’s intensified intervention lowered the frequency of pirate attacks, as well as successful hijacks from its all-time high just a few months earlier. Soon afterwards, European Union and NATO countries including Russia, China, India, and Japan launched twenty-five ships to crack down on pirating in the Indian Ocean alone. They patrolled an area of 8.3 million square miles, the equivalent of one-fourth of the area of Africa. Soon afterward, the E.U launched another program, EUCAP Nestor, with a mission of aiding developing countries with maritime security. By the end of 2012, pirating had hit an all-time low, with only one ship attacked unsuccessfully in the equivalent time frame of twenty-three being hijacked successfully just a year ago in 2011. With the dwindling success of pirates, investors became more and more reluctant to inject capital into the system, leaving the pirates alone in the sea. Pirating had been stopped almost completely, other than the occasional attack from a local fisherman onto foreign non-commercial boats.

Causes for piracy are not completely unknown, and experts have inferred plausible causes of surges in piracy. Many have suggested foreign countries in having a part in starting armed groups of fisherman to patrol the waters, for their own good, as well as the fish’s. It has been reported by the U.S. House Armed Services Committee that for years, foreign boats had been dumping toxic waste illegally in Somali waters, poisoning the fish as well as lowering the fishermen’s ability to gain income. In addition, foreign fishermen stealing fish from the locals also incurred rage, according to Ted Dagne, author of Somalia: Conditions and Prospects for Lasting Peace. Many fishermen started to group up into almost armed militias, defending the Somali waters from dumpers and foreign fishermen. Soon enough, this progressed into hijacking ships to exact justice for the stealing of fish. This almost became an alternative income for many fishermen, and started to spread to commercial ships also. Many coastal communities and leaders approved this, making up the majority of views, according to The Toxic Waste Behind Somalia’s Pirates, a project started in 2010. Almost as a sort of justice that needed to be dealt upon robbing foreigners, fishermen turned pirates started to rob for themselves as earning income due to toxic waste and foreign fishing became increasingly hard.

Many do not know what will happen with the rise and fall and the reappearance of pirating in Somalian waters. If provided a chance by the authorities to transform the process of pirating into a lucrative system once again, European and Asian shipping corporations may have a hard time bypassing the Indian Ocean. Depending on the actions of local authorities, pirating may resurge as locals exploit shipping traffic to support their dwindling incomes. Pirating is not the fantasy that appears in books and movies, but a world of torture, suffering, money, and crime. It is not freedom, but a plague, an awakening entity ready to haunt the sea.