The Zika Virus: A Closer Inspection

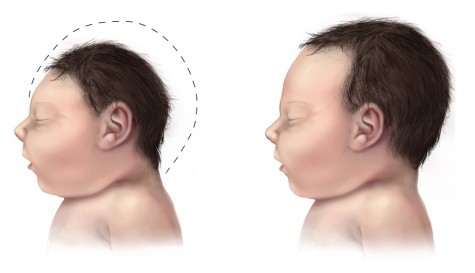

The world is cowering before a tiny insect—the mosquito. It is the vector of an increasingly threatening disease whose geographical range has expanded well beyond the initial point of outbreak—Brazil, 2015—and infected a total of thirty-three countries thus far, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). The Zika virus has been causally linked to birth defects, such as microcephaly, as well as Guillain-Barré syndrome, and El Salvador—one drastically affected nation—has called for a hiatus in childbearing until 2018. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) has also responded to the general medical threat, by enacting level one and two travel health notices, and the WHO has declared a public health emergency of international concern—a designation only given three times before, to Swine flu, polio, and Ebola.

The Zika virus is not new, however this is the first global-scale outbreak since its identification in 1947, during a study of sylvatic yellow fever in Uganda’s rhesus monkeys, the WHO reports. Scientists detected human infections in 1952, placing the virus in a category of pathogens known as zoonotic diseases—transmissible between animals and humans. The current animal carrier is the Aedes aegypti mosquito, which is also responsible for the spread of yellow fever and dengue. According to the Washington Post, this insect resides in every nation in North and South America, excluding only Canada and Chile. In combination with the fact that Zika is a relatively new virus to currently threatened regions—where populations lack widespread immunity—the resultant general opinion is that it will likely spread “explosively.”

Since its emergence in 2015, the CDC and the WHO, along with other national and international health organizations, have been charting the virus’ global progress and making predictions about what regions it will impact the most as it spreads. The areas considered most vulnerable are those with sub-tropical climates and/or concentrated centers of population where mosquito protection is limited for one reason or another.

While travel warnings can help keep many safe, there is a blossoming new concern in the mix—the 2016 Summer Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro. Many of the athletes traveling to the events to compete in just a short time are in the high-risk category of the population, namely women who are pregnant or expecting to become so in the future. According to the Chicago Tribune, efforts to combat possibilities of illness are already being implemented: the United States Olympic Committee (USOC) has announced the future hiring of two infectious disease specialists—at least one of whom will be female—to monitor Olympic preparations and safeguard athletes throughout the games.

Concerns about disease have already been in play for some time, as pollution led to the rise of deadly bacteria in water venues set to be used in August, and the dengue virus is also resurfacing alongside Zika. However, the official word for now is that the Games will proceed as planned, especially considering August ironically marks the height of the Brazilian winter. As Mario Andrada, communications director for the Brazilian Olympic Committee, emphasized in a statement, “The rate of infections due to mosquito bites drops drastically and virtually reaches zero” during that time.

The USOC’s approach to combatting the threat of Zika is not the only one in play, as the Washington Post reports, South American nations such as Brazil and Columbia are concentrating resources and manpower in national efforts to support health workers. However, with as little knowledge as is available at present, most efforts are focused on research: what is it, how is it spread other than via mosquito, and what tests can be used to differentiate it from the other viruses also spread by the Aedes, such as dengue. Ebola, the most recent infectious disease classified as an international health emergency, was much better researched in comparison, even if the response time to contain it was much slower. As Bruce Aylward, a WHO official leading the Zika response, was quoted as saying, “This is the classic ‘building your boat as you sail it.’ People said that about Ebola, and that was trying to get a bigger sail on the boat. Here we’re still stitching the sail, and we’re not quite sure what kind of sails you really need.” There is currently no vaccine to prevent a Zika infection, and no specific treatment.