Astrocytes For Your Mental Health

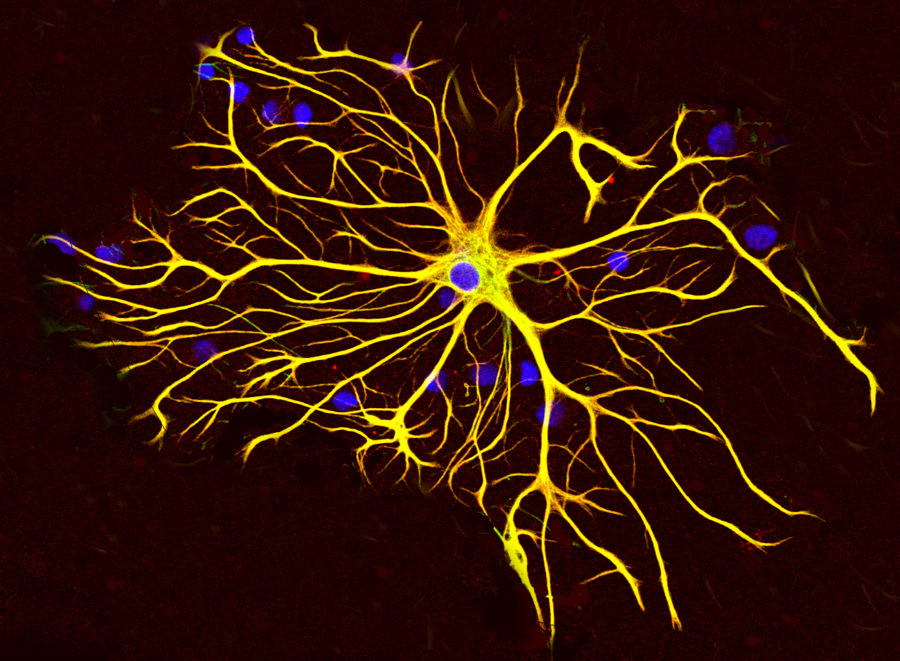

Astrocytes are a type of star-shaped brain cell that supports neuron function by providing energy to neurons and supporting neurotransmission.

Depression is an unfortunately common mental health condition that, despite the social stigma that claims otherwise, has a concrete scientific basis. New research suggests that people with depression have distinguished features in their brains—fewer astrocytes.

Astrocytes are a type of star-shaped brain cell that supports neuron function by providing energy to neurons and supporting neurotransmission (the relaying of brain signals), according to Liam O’Leary, the study co-author and a doctoral candidate in the Department of Psychiatry at McGill University in Montreal. A study published on February 4th in the journal “Frontiers in Psychiatry” highlighted the difference between the cellular composition of the brain in adults who committed suicide caused by clinical depression versus those who died suddenly due to other causes. The study has suggested that the number of astrocytes are highly correlated to depression since without these cells, important functions of the brain are deterred. According to O’Leary, the reduced amount of astrocytes in an individuals’ brain have negative effects. For example, since the brain regions studied in the new research make up a circuit that is crucial for functions like decision making and emotional regulation, a lesser number of astrocytes can worsen symptoms of depression. Without the astrocytes, neurons will not function in these brain areas and cause consequences in patients’ emotional regulation and decision making. Naguib Mechawar, the other co-author and a professor at the Department of Psychiatry at McGill University adds, “We found a reduced number of astrocytes, highlighted by staining the protein vimentin in many regions of the brain in depressed adults”.

According to O’Leary, past studies that have linked people’s postmortem brains with depression have already proven that some brain regions had fewer glial cells, which is a group of “helper cells” in the brain, where the astrocytes belong. However, in these studies, it only confirmed the reduced numbers of astrocytes in areas such as the amygdala, where GFAP proteins are produced. The new study conducted by O’Leary and Mechawar was able to confirm the reduced numbers of astrocytes in other regions of the brain: the prefrontal cortex, thalamus, and caudate nucleus. O’Leary also commented how several depression researches may only look at one region in the brain, but the new research is unique and extremely significant because it was able to confirm the reduced numbers of astrocytes in different brain regions. Jose Javier Miguel-Hidalgo, a professor of psychiatry and human behavior at University of Mississippi Medical Center says, “It seems that there is a pretty widespread change in those astrocytes no matter how you look at them.” Even though this new research was able to confirm the correlation between the number of astrocytes and one’s mental health, O’Leary also comments how there needs to be more research to find whether or not people with depression lose these brain cells over time, or if they have fewer of them to start with.

Researchers hope that these new discoveries will guide them toward future treatments for depression. Mechawar comments, “The promising news is that unlike neurons, the adult human brain continually produces many new astrocytes. Finding ways that strengthen these natural brain functions may improve symptoms in depressed individuals.” If drugs that counteract the loss of astrocytes are developed, it may serve patients to lessen some consequences from depression, and potentially even help patients to recover more effectively in a shorter period of time. In addition, some research has already discovered that antidepressants can boost astrocyte function and increase the numbers of these cells in animal models of depression, according to Miguel-Hidalgo. However, since this study was only conducted using male subjects, Mechawar and O’Leary are looking to repeat this study on female subjects since neurobiology of depression can be different across genders. Further studies are needed to correct depression treatments utilizing astrocytes and to confirm if these new treatments will be safe for humans as well. However, Miguel-Hidalgo also states, “Can we use that information to design treatments which are specifically targeting astrocytes? The future will say, but I believe the possibility is right there,” Many researchers, like Miguel-Hidalgo, are extremely hopeful that this new information revealed by this recent study will help develop a new, effective way to treat depressed patients. As depression is becoming a major problem every year, especially with the onset of the pandemic, these newly established treatments will be able to help millions of struggling patients of all ages.