Does Student Debt Involve Systematic Racism?

Student debt is commonly assumed to be a generational issue, affecting twenty and thirty-year-olds as they enter adulthood. While it’s true that most young individuals are dealing with large amounts of student debt that their parents and elder siblings have never had to deal with, race is likely one of the most important elements in determining a borrower’s student loan experience.

Ky’Lend Adams can attest to these racial inequalities. Adjusting to life as a young adult has been much different for the twenty-four-year-old living in New York City than it has been for many of his white contemporaries. “When people graduate they think, I’m going to take a trip, I’m going to take a cruise, I’m going to go abroad,” said Adams, who is African-American and graduated from George Mason University last year. “That can’t be my priority.” This is because he has about $90,000 in college debt to deal with.

Understanding the perspectives of borrowers of color, such as Adams, is critical to comprehending how our student loan system fails to deliver on its promise of making higher education, along with the advantages that come with it, more accessible. While a college degree is an investment that pays off, often with over 55k annual salaries, the danger of it not paying off is significantly greater for students of color and black students specifically. The reasons behind this are numerous, but they likely derive from America’s history of institutional racism. The American historical precedent of prejudice and discrimination has limited the resources available to black families to pay for college, thus increasing the likelihood that black students will attend colleges with limited resources and be targeted by predatory colleges. These colleges recruit students with false promises of providing them with well-paying jobs and meaningful careers, with the point to recur students federal student aid, while still facing barriers blocking admission to wealthy, elite, higher education institutions. They’re also more likely to struggle with debt repayment when they graduate. Student debt is “both a cause and consequence of racial inequality”, according to Jason Houle, a sociology professor at Dartmouth College who has researched how borrowers’ experiences differ by race. Much of the variance in borrowers’ experience stems from the wealth gap between black and white households. Because of the profound income difference, black students are more likely than white students to borrow for college, and they borrow substantially more.

Student debt is “a fact of life for students of color if they want to attain higher education,” said Mark Huelsman, associate director, policy and research at Ohio Northern. He added, “The bigger problem is that the payoff to a college degree is lower for students of color than it is for white students.” This tendency is part of a larger trend in higher education and other aspects of economic and financial life known as predatory inclusion, according to Louise Seamster, an professor of sociology and African-American studies at the University of Iowa. She characterizes it as “a turn from former exclusion of a marginalized group, to inclusion, but on terms that negates the benefits”.

In higher education, predatory inclusion manifests itself in a variety of ways. One example is for-profit institutions that serve students who have traditionally been barred from higher education — but with a subpar product. Consumer activists have been demanding data from the government over the past few years to see if debt collectors of student loans treat borrowers of various races differently, a pattern that has been well-documented in other sectors of consumer lending.

However, according to Seamster, executives and higher-education officials aren’t the only ones who contribute to the disparity in student-loan outcomes between black and white borrowers. Higher education has become less of a public benefit just as a college degree is becoming more important than ever to succeed in today’s market and more students of color are enrolling in college. State governments are less eager to invest in public institutions in order to keep student prices low.

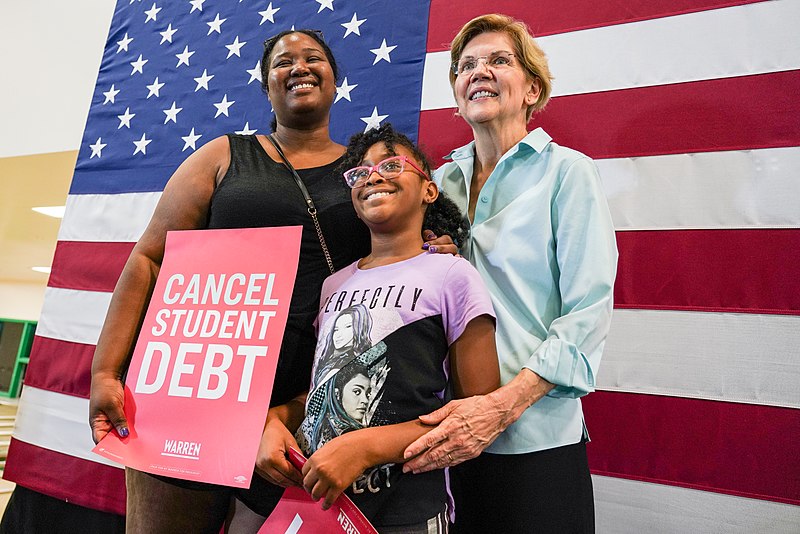

Policymakers have also begun thinking more critically about how the student loan experience differs by race in recent months. It’s a discussion that experts believe is critical to comprehending the student debt situation as a whole, as well as possible ways to fix this issue.