Adios, Alzheimers

In 2020 alone, around 5.8 million Americans were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. The CDC stresses this number and describes that if the trend continues, it is projected to triple to 14 million people by 2060. To put it in simple terms, this is about 3% of the population. This may seem like a temporary problem at face value, but when considering the severe symptoms of Alzheimer’s, the effects are much more obvious.

Alzheimer’s disease, in simple terms, is a type of dementia that begins with mild memory loss and progresses into a severe kind– common symptoms might include the inability to carry a conversation and properly respond to the environment. Not only does this disease have a debilitating impact on the person unfortunate enough to contract it, it also has severe damages upon their loved ones.

For example, Mike Balson, a strong elite athlete who was eventually diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, sat down with his wife Julia Balson in an interview with the Alzheimer’s Association. They describe several changes in their relationship after being diagnosed, including the fact that they have begun attending support groups and becoming more dedicated to their faith. Their life would never be the same, but they were learning to work through the consequences and understand how the circumstances can be easier in the future.

Scientists, understanding the severity of these issues both for the person who is diagnosed and their loved ones, have done extensive research into various cures or medications. The first drug for treatment was initially approved in 1993, aiming to target Alzheimer’s memory and thinking symptoms. Many other scientists bounced off this treatment, and 4 other drugs were approved within the following ten years.

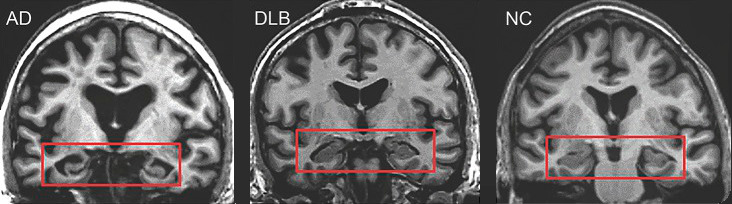

Currently, in 2023, research continues to advance. Most notably, a group of neuroscientists, led by researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, were able to develop a test that would detect a marker of Alzheimer’s just by using a blood sample– this also meets all requirements specified by the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association. The most accurate way to check for Alzheimer’s in the present day involves neuroimaging through MRI and PET scanners. According to the University of Pittsburgh Medicine, these tests are extremely expensive and require large amounts of time to schedule. Additionally, they are not very accessible in second or third-world countries, and even certain places in the United States lack access to these high-end machines.

Testing for Alzheimer’s using blood tests has definitely been experimented with before, but they haven’t been able to detect all three requirements specified by the National Institute– including the presence of amyloid plaques, tau tangles, and neurodegeneration of the brain. The most recent hurdle has been detecting signs of neurodegeneration that are particularly impacting the brain rather than other parts of the body (which can provide incorrect information). An example of this would be that blood levels of neurofilament light, a sign of nerve cell damage, are frequently elevated with the onset of Parkinson’s and other neurological diseases, but also Alzheimer’s as well.

Thomas Karikari, a researcher at the University of Sweden, and his team were able to design a special antibody that would bind exclusively to BD-tau, rather than other tau proteins from outside of the brain. The team hopes that this could improve clinical trial design, while also making the blood tests more specific to Alzheimer’s and more reliable.

Karikari and his team are planning to conduct further clinical trials on the validity of the blood test, and hope that the biomarker results are applicable to people of all backgrounds. If the testing is successful, this method has the potential to become available for widespread prognostic use– revolutionizing Alzheimer’s diagnosis as it is known now.