In a striking revelation of a scene from a horror movie, researchers at the University of Maryland at Baltimore County recently stumbled upon a phenomenon undiscovered: a virus latched onto the neck of another virus.

The research team has understood the symbiotic relationship between the so-called “satellite” virus and their host organisms, relying on a “helper” virus for replication inside cells. However, recent findings have unveiled an unprecedented occurrence of a satellite virus that attached itself to the helper virus.

Published in the Journal of the International Society of Microbial Ecology, co-authored with colleagues from Washington University, the researchers describe the intricacies of this peculiar interaction actions of the satellite bacteriophage, a virus that infects bacteria cells.

According to the Washington Post, bacteriophages “also called simply phages, are among the most abundant organisms on Earth. There can be millions in a gram of dirt.”

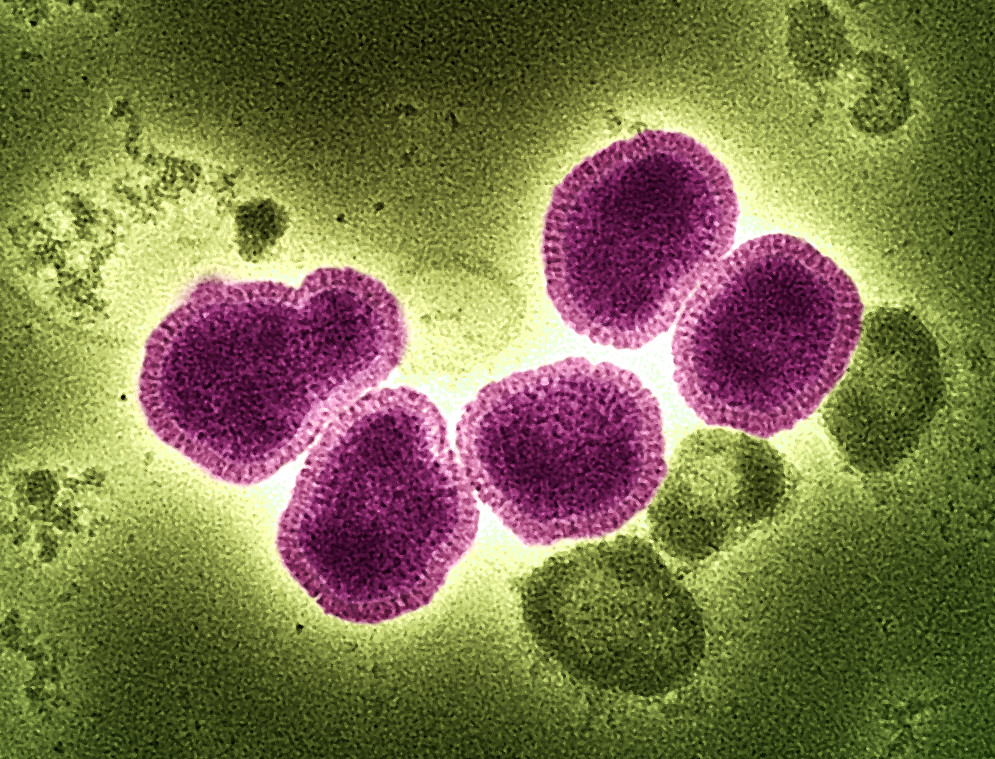

Tagide deCarvalho, assistant director of Baltimore University’s College of Natural and Mathematical Sciences and the paper’s first author, captured images that showed that 80% of the helpers had satellites on their necks. As described by senior author Ivan Erill, professor of biological sciences, even those without a visible attachment displayed tendrils, described as “bite marks”.

Additionally, the researchers explained the genetic mechanism at play, expressing that most satellite viruses possess a gene enabling integration with a cell’s genetic material upon entry. This integration facilitates reproduction whenever a helper cell enters, as the host cell replicates the satellite’s DNA and its own during division.

The Washington Post reveals that scientists theorize that a, “small virus, called MiniFlayer, lost the ability to make copies of itself inside cells, which is how viruses reproduce. So evolution devised a clever, parasitic workaround. MiniFlayer takes advantage of another virus, dubbed MindFlayer, by grabbing onto its neck, and when they enter cells together, MiniFlayer utilizes its companion’s genetic machinery to proliferate.”

Researchers assume that it integrates with the host cell because it carries no gene. Due to this, it stays close to the helper. In a statement, Erill expressed that, “Attaching now makes total sense… because otherwise, how are you going to guarantee that you are going to enter into the cell at the same time?”

Erill explained to the Post that, “viruses will do anything. They are the most creative force of nature. If anything is possible, they will come up with a way to do it. But no one had anticipated that they would do something like this.”

The Baltimore research team came across the MiniFlayer by chance. While the University of Pittsburgh lab initially flagged the sample containing MiniFlayer as contaminated, the researchers were curious. They tried again and had the same result.

Recognizing the need for more specialized investigation, they sought for deCarvalho, as he had access to a transmission electron microscope.

The team’s discovery now sets the foundation for future research on how the satellite attaches, how common of a phenomenon it is, and much more. “It’s possible that a lot of bacteriophages that people thought were contaminated were actually these satellite-helper systems,” Carvalho suggested. “So now, with this paper, people might be able to recognize more of these systems.”