For a long time, I’ve romanticized Western journalism. To me, publications like The Atlantic and The New Yorker were paragons of deep, varied opinions—meanwhile, The Intercept, ProPublica, and the late Buzzfeed News were some of the very best investigative reporting available. Even general outlets like The New York Times and BBC, for all the slight biases dispersed under their images of objectivity, were solid, wide sources of information.

Gaza changed things. Over the past 3 months, the Western reporting landscape, especially that of the U.S., has been catastrophically disappointing. Publications have mobilized in wartime support unseen since 2003’s Iraq, eschewing the morals for which they were so highly prized around the world. Bias, censorship, and blatantly constructed narratives take root throughout publications—but perhaps most severely, the idea of press protection seems all but completely dissolved. In many senses, the past weeks have brought the ideal of Western journalism to its deathbed.

To begin deconstructing Western bias on Palestine and Israel, there is really one foundational issue to start with—a painstaking avoidance of context. Western journalism on Palestine and Israel is historically reflexive; as a 2021 letter by high-profile journalists states about U.S. coverage, “reporting wanes considerably when Israel halts its airstrikes. Palestinians are ignored in so-called times of ‘peace’ despite attacks and other hostile aspects of life under occupation continuing after the ceasefire.” In essence, Palestine and Israel are ignored until the latter intensifies its attacks on Palestine, or until the former’s militia groups—reactively or not—attack Israel.

The glaring flaw of this reaction-based reporting is Palestinians’ day-to-day lives—which reputable human rights organizations like Amnesty International recognize as “apartheid” on Israel’s behalf, in which Palestinians are subject to “administrative detention, torture, unlawful killings…and the denial of basic rights and freedoms”—remain unrecognized. This goes double for the Gaza Strip, widely-recognized by human rights organizations and Western publications as an “open-air prison” which civilians are not allowed to enter or leave, and where supplies, even before Israel’s human rights catastrophe of a blockade, are severely limited.

So, when October 7th’s attacks, or the responding destruction of Gaza, or any number of altercations break out, they are reported from an inherently problematic perspective. A return to status quo is presented as the ultimate humanitarian goal for conflicts between Palestine and Israel. But in reality, a return to normal for Palestinians is a turn back towards the brutal, unrelenting conditions of occupation—certainly nothing amounting to peace. Today, this fallacy is most apparent: even as Western nations like the U.S. tone down their bizarre censorship of the word ceasefire after October 7th, little understanding is being cultivated of what a ceasefire would even mean anymore for Gaza. Half of all residential units have been damaged in the strip and, on top of the nearly 19,000 already dead, the growing count of 50,000 injured Gazans would likely find treatment nigh impossible even after ceasefire, given Israel has continued to attack Gazan healthcare facilities, leaving less than half of Gaza’s 36 hospitals functional.

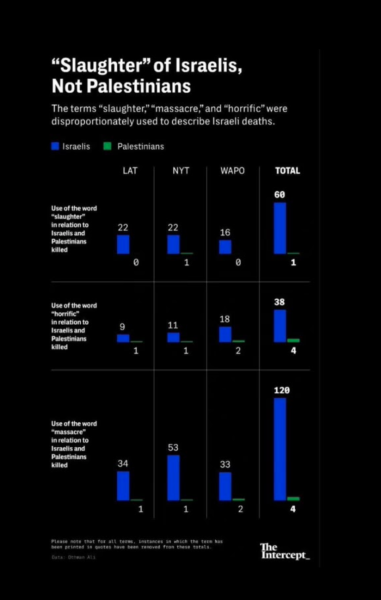

But context is only the backdrop of a journalist’s work; articles themselves are what define reporting in an area. And the bias of Western reporting on Gaza has been catastrophic. Language plays a key role in facilitating Western outlets’ downplay of deaths in Gaza, compared to those in Israel—while October 7th’s attacks are reported across the board as killings by Hamas, headlines by many outlets actively avoid mentioning Gazans being killed, or the Israeli army’s culpability.

Countless examples reflect this trend. One is a now infamous December 3rd print headline in The Washington Post, on four infants killed in Gaza due to Israeli bombardment leaving their hospital unable to operate on them, which read “Four fragile lives found ended in evacuated Gaza hospital.” Rather than Israeli airstrikes and resulting healthcare shortages killing infants, it is “fragile lives” which are seemingly by coincidence “found ended.” The digital version of the headline does mention Israel’s role in the deaths, reading “Israel’s assault forced a nurse to leave babies behind,” but it still refuses to use the word “dead” or “killed,” instead continuing “They were found decomposing.”

The New York Times presents some of the strongest cases of biased headlines. An October 31st headline read, for example, “A Deadly Airstrike, and Gazans at the Breaking Point,” leading into an article which reported on Israel’s targeted bombing of Gaza’s largest refugee camp (an act which, in a staggeringly common disregard for civilian life, the Israeli military justified with the claim that one Hamas commander and tunnels were being targeted in the airstrike, amongst at least 50 other civilians). The New York Times’ headline seems to purposefully avoid implying any culpability for the airstrike, despite Israel’s military open admission of the attack, and is deeply vague on the scale of civilian casualty, simply describing it as “deadly.” In a similar vein, the bombing of Al Maghazi refugee camp on November 5th saw The New York Times reporting “Explosions Gazans Say Was Airstrike Leaves Many Casualties in Dense Neighborhood.” Again, the headline is strangely vague, with a piece by writers’ community Global Voices pointing out how the headline unnecessarily casts doubt on and avoids stating blame for the bombing, especially given it was “one of three airstrikes hitting refugee camps in Gaza within a 26-hour window.”

The deeply flawed reporting on Gaza has not been lost on Western journalists, though their voices have either been ignored or actively suppressed. A letter signed by nearly 1500 journalists throughout the U.S. published November 9th accused Western reporting of painting October 7th as the start “of the conflict [between Palestine and Israel] without offering necessary historical context,” using “dehumanizing rhetoric that has served to justify ethnic cleansing of Palestinians,” and avoiding “precise terms that are well-defined by international human rights organizations, including ‘apartheid,’ ‘ethnic cleansing’ and ‘genocide.’”

Since the letter was published, the LA Times blocked all its journalists who signed from reporting on Gaza for 3 months, and over 30 journalists reportedly asked to have their signatures removed for fear of reprisal by their employers.

Frustration has also built in Western outlets outside of America; on October 25th, British newspaper The Times reported that BBC staff were “crying in lavatories [at work],” and that journalists had sent an internal email concerned the studio was “treating Israeli lives as more worthy than Palestinian lives.” Other BBC sources corroborated “the mood from a lot of people in the building is that we aren’t getting the coverage right.”

But the final, massive nail in Western journalism’s coffin has been the all-but absent concern for physical press protection. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, the month beginning on October 7th was the deadliest for journalists since the beginning of their coverage in 1992. As of December 16th, 57 Palestinian and 3 Lebanese journalists have been reported killed under Israeli bombardment, as well as 4 Israeli journalists in Hamas’ October 7th attacks.

Over its bombing campaign in Gaza, the Israeli government has openly made calls for the murder of Gazan journalists, who Reporters Without Borders report have been killed at a rate of more than one a day in the month of Israeli airstrikes following October 7th. On November 9th Danny Danon, a member of the Israeli parliament, posted calling for the “elimination” (translated by Reporters Without Borders from Hebrew) of photo journalists who covered the killings on October 7th—this came off Israeli government claims strongly refuted by outlets like Associated Press, Reuters, and The New York Times that journalists in Gaza were aware of October 7th’s attacks in advance. Israeli Defense Minister Benny Gantz also posted in Hebrew that such journalists were “no different than terrorists and should be treated as such.”

Although now at an unprecedented scale, this is not the first time Israeli forces have actively killed journalists reporting on Palestine. 2022 saw the murder of Al Jazeera’s Shireen Abu Akleh while covering an Israel Defense Forces (IDF) raid on the Jenin refugee camp. For some time Israel pinned the blame on Palestinian gunmen, but after overwhelming investigative evidence, conceded that it was in fact an Israeli sniper.

In conclusion, Western reporting on Gaza has been a tragedy. Palestinian deaths have been devalued while the conflict is ripped from context, frustrated journalists are censored in efforts to speak truth to power, and overwhelming numbers of dead reporters in Gaza pile up as Israel is not held accountable for disregarding the crucial standard of press protection.

And, as someone who previously looked up to the West’s standards of journalism, I’m left with massive amounts of baggage. The reporting trends aren’t all surprising to me—for decades, Western media has been documented in its historical biases when reporting on Palestine. But the current scale and uniformity of reporting today to me is disturbing; especially pressing is the idea that, given the opportunity to speak against the open biasing and murder of journalists, the Western media has instead chosen to suppress voices within itself that call out for their peers’ safety.

One way or another, what is happening in Gaza won’t last forever. Publications will eventually write in retrospect of events occurring now, likely taking much more responsibility in looking back—as with Iraq—than when the matter is morally pressing. But for once-hopeful readers like myself, something has given away. The glowing, long-hallowed values of Western journalism have dimmed to a twilight. And in many ways, there is a distinct sense that this institution of ours—one that has built itself on solemn, impartial, and unrelenting work for the greater good—has begun to fade away from inside Gaza.