It’s the last essay before the final. You have a last day to write it — 20 minutes, realistically; it’s 11:39. Your grade hinges on the 89 percent border. What do you do?

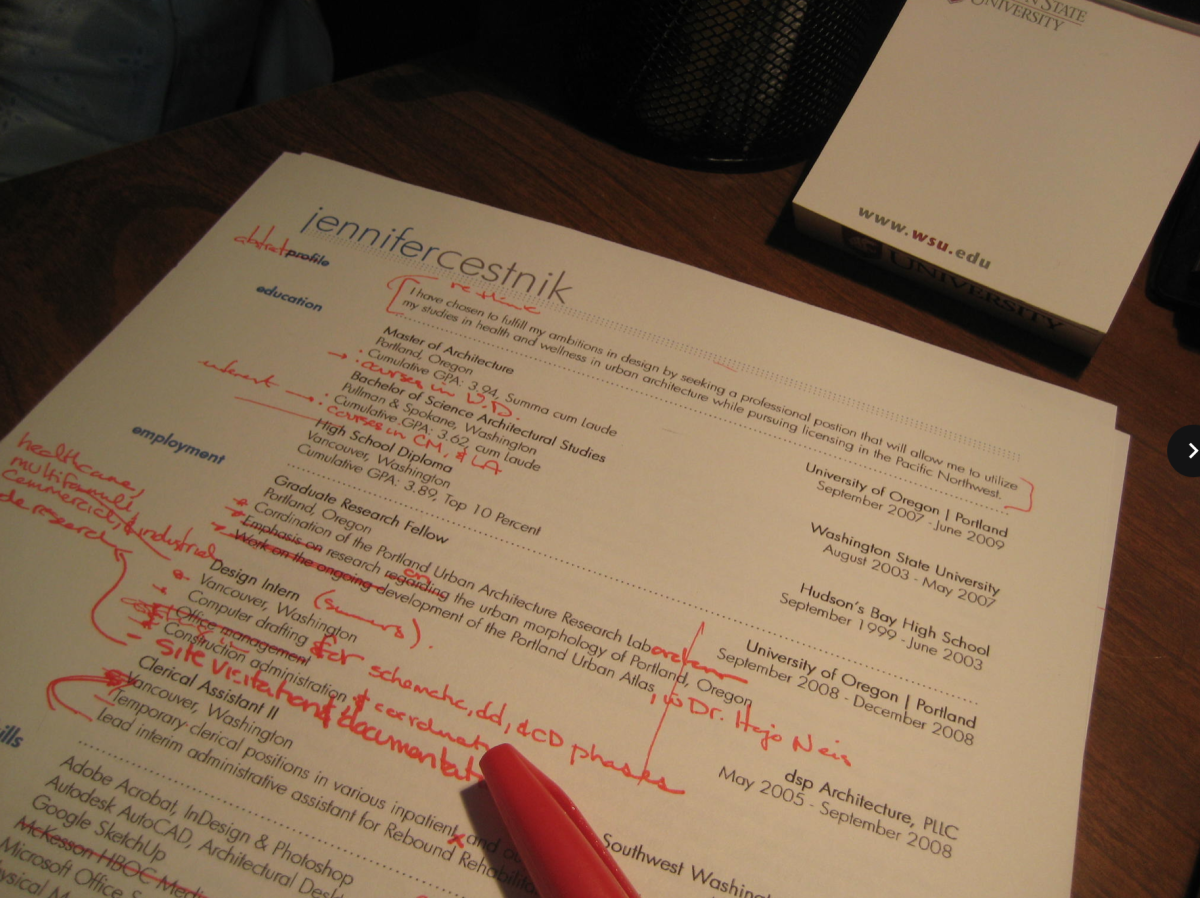

In many classes, this is about the time you start typing a heart-wrenching email or suspiciously autofill OpenAI in the search bar, depending on your general moral character. You may be encouraged to avoid procrastinating in the future, but whatever academic lessons the essay’s construction was meant to teach are likely gone. Unless, of course, your class has revisions.

The case for revisions is simple: give students a little leeway on their assignments, and they’ll learn more from the work they produce. However, despite its potential benefits, revisions are not without trouble. Issues like increasing student laziness and teacher workload result in revisions’ inconsistent inclusion across classes — none of the students interviewed for this article reported they had more than 3 classes with revisions in their schedule this year. When holistically understood, though, revisions may end up seeming less problematic than assumed.

Before discussing the strengths of revisions, it’s crucial to understand the arguments against them. Mr. Jackson is an AP Literature teacher who allows revisions on many of his assignments, albeit under certain restrictions. “When we’re doing long form writing, students will write first drafts…and get feedback, and then do revisions, and turn in the second draft.” But on quizzes and tests, Mr. Jackson sets limits: for vocab quizzes, students need to receive below a C to unlock revisions, and can only revise up to a B. Mr. Jackson’s policy reveals the first, major concern many teachers hold about revisions: “Students who have As or Bs on the quiz already know the majority of the material, so they don’t necessarily really need to do the retake. It becomes less about the knowledge then, and more about just the grade.”

This sentiment of revisions causing students to focus on grades or previous units is present amongst teachers of other classes as well. A prime example is math. Given topics are often built on, learning subjects on time is often crucial in the class. Potentially as a result, one finds that revisions are especially scarce amongst Wilcox’s math classes.

That being said, many students advocate strongly for revisions’ benefits despite these flaws. Zane Sharif, a junior at Wilcox, has revisions in 3 of his classes. He says “They [revisions] help a lot. A lot of it is the difference between getting a higher letter grade obviously, if I’m on the cusp of getting an A or something. I also get to learn a lot more than I did previously.” He points out that, in written assignments for example, revisions help him see issues with his writing he hasn’t “seen before when I was previously writing the final draft.”

Students also commented on the idea that revisions cultivate an unhealthy focus on grades. Samuel He, another junior, believes coming back to an assignment helps students focus specifically on, “what you did wrong, so you can fix that.” He disagrees with revisions leading to students being hung up on past units, arguing “They [students] should focus on past stuff…it doesn’t [hang them up], because it helps them review.”

In an example which exemplifies revisions’ potential for sparking student growth, AP US History teacher Ms. Scott interviewed on a revision policy on tests she only “started…last year.” She mentions that integrating the policy has already brought visible improvements: “I have noticed that kids are more relaxed taking the tests, and they ask more questions…and one of my students I felt like did so much better on the AP exam because, every test she came back, and we talked about all the questions.”

Ms. Scott’s recently implemented policy has also shown some of the issues which have been held against revisions. She points out the problem of student apathy, saying “I’m gonna have it cut off…[after] a certain amount of time…I think I’ve been a little too lenient.” She also repeats the sentiment that revisions inspire a focus on grades, explaining that her policy only gives half credit for revised answers.

And yet, the comments of juniors like He and Sharif reflect that revisions are valuable to students for academic growth beyond just grade-hunting. Issues like apathy and obsession do exist with the policy, but the somewhat undue emphasis placed on them has resulted in a stark lack of revisions across many students’ schedules. The framework from which revisions are assessed should be shifted to reflect their benefits in the eyes of students — many of whom are genuinely seeking growth — as much as the aforementioned downsides. That way, the policy can be understood and implemented more holistically across classes.