On October 27, nearly ten thousand people crowded New York City’s Washington Square Park to see the entries for a community-organized “Timothee Chalamet Lookalike Competition.”

Bringing together contestants from across NYC, each supposedly bearing resemblance to Timothee Chalamet, the audience searched for the closest match—someone with an uncanny likeness to Chalamet, embodying their admiration for his conventional attractiveness.

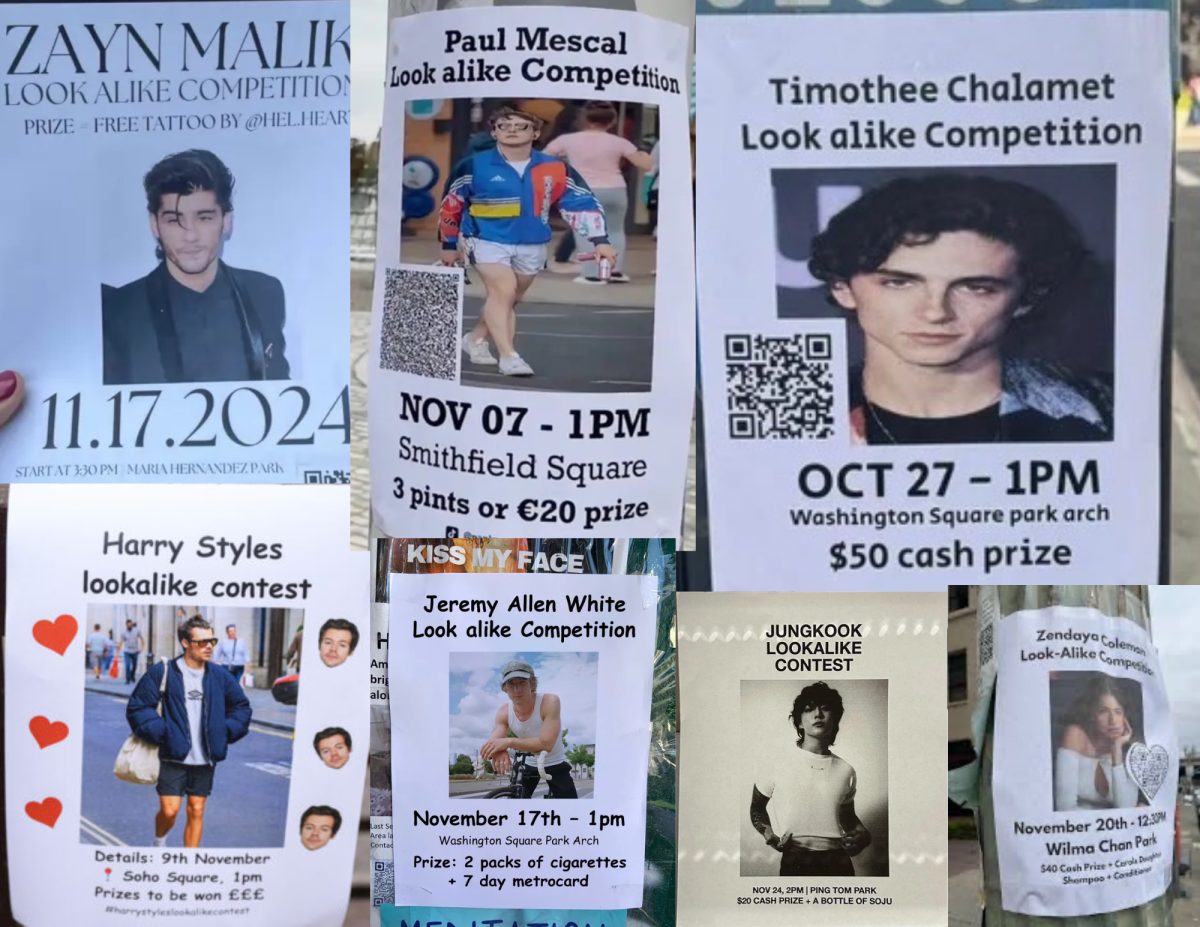

Since NYC’s massive gathering of Timothee Chalamet’s fans, similar “Lookalike Competition” events have emerged across the world, fixating on admired, “heartthrob” public figures—Paul Mescal in Dublin, Dev Patel in San Francisco, Jeremy Allen White, Jungkook in Chicago, and many more. Flyers advertising lookalikes competitions for various celebrities have appeared across major U.S. cities. These competitions continue to draw large crowds composed of widespread fanbases for their celebrity of choice.

Despite the initial use of traditional paper advertising or flyers on lampposts, social media and online fanbases have contributed most to the exponential popularity of celebrity lookalike competitions. From digitizing of spotted flyers or digitally documenting events shared with online audiences, the rising celebrity lookalike competitions have acquired a broader range of judges among virtual atmospheres.

However, supplementing celebrity lookalike competitions with social media dominance has only further fueled social media’s pre-existing problem: worshiping immaterial likes, clicks, and hits.

Under social media’s integration into our lives, users have adopted an instinctive online transparency, documenting and sharing daily interactions to social media audiences. But transparency instead becomes driven by user engagement under an environment rewarding digital validation—translated through likes, comments, and shares. What was intended to be innocent online transparency shifts into a desperation for conformity guided by a core question: “How do I let others perceive my life as more interesting?”

Attending celebrity lookalike competitions has provided the remedy for such a vague question, granting engagement-driven users with the validating user interactions. With the initial surge in engagement with celebrity lookalike competitions, stemming from NYC’s Timothee Chalamet lookalike competition, consequent competitions organized for similarly mainstream public figure comparisons. From a simple TikTok search, “celebrity lookalike competition,” videos posted within the last twenty-four hours have already obtained three-thousand to fifty-thousand likes, despite approximately forty-one days since the initial trend’s surge. User attendance has become the unspoken tool for capitalizing from, molding the perfect atmosphere to maximize content engagement and to guarantee audience traction from the shared celebrity admiration among dominating fan bases.

The rise of celebrity lookalike competitions has also proliferated the issue of parasocial relationships: an audience overfixation on celebrities, investing misdirected emotion, interest, and time into celebrity praise. For lookalike competitions particularly, audiences have begun using these fanbase gatherings as matchmaking opportunities, seeking partners with one specific criteria: resemblance to their celebrity idols. Among the widespread advertising of various lookalike events, surfacing mock-up flyers have substituted typical flyer phrasing for gathering contestants to “____ lookalike competition at my house.” These mock-up flyers, despite their satirical nature, contribute to a problematic attitude allusive to parasocialism. Each subtle joke masks a desperation for personal celebrity relationships within seeking romantic partners. But where is the boundary between admiration and obsession?

Katie Pham, Wilcox senior, comments on Chalamet’s flocking fans: “Okay, he has played some great characters in some great films, but why are you foaming at the mouth for him? Not even him, but some random dude off the street that could maybe be his tenth cousin.” Responding to the rise of lookalike competitions used as matchmaking opportunities, Pham continues, “ searching for someone exclusively through similar appearances is wild. Y’all need to go outside, and attending a lookalike competition doesn’t count.” Beyond Pham’s harsh criticism, there is an underlying truth: merging parasocialism and “lookalike matching making opportunities” creates a toxic atmosphere where people seek partners solely based on appearances, but more specifically based on resemblance to celebrities. Fans’ passionate desires for celebrity similarity among daily encounters ultimately restricts the pursuit for forming genuine connections.

Beyond the social media fixations lookalike competitions foster, audience pursuits for matchmaking opportunities reveals an audience desperation for closer connections with idolized celebrities.