Tiny Homes for the Homeless in San Jose

In the 2015 Point-in-Time Census, 4,063 homeless people were reported in San Jose. Of these people, only 31 percent are sheltered, living in emergency and transitional homes. The other 69 percent remain unsheltered. Even worse, this number is most likely an undercount of the homeless population. Hence, the amount of people on the streets displays our city’s housing problems. In order to decrease this shelter crisis, the city of San Jose plans to create tiny homes for the homeless by evading the state’s confining building codes.

A recent bill signed into law on September 27 by Governor Jerry Brown signals the start of Mayor Sam Liccardo’s revolutionary idea of tiny homes. “It was huge for the governor to sign this because it’s outside-the-box and no one else has done it,” announced Assembly member Nora Campos. “Other big cities like San Francisco and Los Angeles will be looking at what we do here. We had to do something because what we were doing wasn’t working.” The plan is set to take effect in January 2017 and will end in five years in 2022.

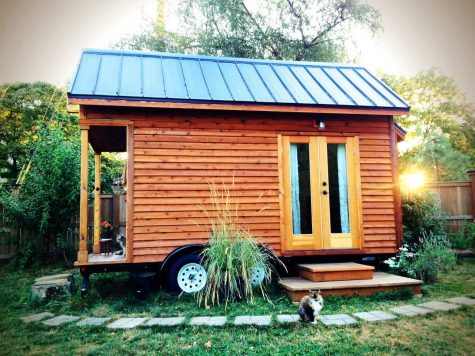

The law dictates that single-person “emergency shelter cabins” must be at least seventy square feet while those for couples must be no less than 120 square feet. Each unit must be insulated, wired for electricity, include at least one lightning fixture, and be topped with a weatherproofed roof, plus a privacy lock. Seeing as to how tiny houses have a 200-300 square feet size they very easily fulfill this condition of the law. According to city documents, a half-acre piece of land could house up to twenty-five people inside twenty of these units. Regardless of the sizes, these houses are far better of a living place than on the streets, as homeless San Jose resident Monica Fuentes comments. “You can’t live your life out here without having your stuff stolen,” she says. Furthermore, it will provide “a stable place people can live and stay at while they’re waiting to be placed in a permanent home,” says Ray Bramson, San Jose’s homeless response manager. Hence, these homes will provide a temporary stopping and transitional point until San Jose can build its planned 500 or more new and affordable housing apartments during the next five years.

The law allowing the plan to take action has another restriction with a bigger challenge — the location. It states that only city-owned or city-leased land may be used. The next step is deciding where to have this community of tiny homes and what it will look like. The future location is yet to be determined, but the city is planning to hold a competition for the designs of these new “tiny” homes. The goal, Bramson said, is to focus on innovative features, cost effectiveness, and the ability to easily duplicate the homes. The practicality of the program will be evaluated in 2022, when the law allowing their construction will be suspended.

Fortunately, the wall city officials had first hit in the summer of 2016, encountering rigid building and health codes, has now been successfully surpassed all thanks to Assemblymember Nora Campos’ Assembly Bill 2176. City leaders can now see if the idea that has worked in other various parts of the US, can work here, especially since other housing ideas the city is pursuing—using old motels for apartments or building new ones—could take years to develop.

This idea of “tiny homes” first originated in Portland, Oregon when a sixty-year-old man who built a wooden frame around his tent home, creating a small living space inside. Many others followed, eventually establishing Portland’s Dignity Village, accommodating approximately sixty tiny home structures. Other cities, including Austin, Texas and Olympia, Washington have followed suit, and San Jose plans to be the next. Architects have updated this on-the-spot makeshift idea, creating shed-sized homes, often 300 square feet or less, with a locking door, closets, full-size beds, and small kitchens that can house up to two people.

The City of San Jose has been looking into models that also include composting toilets and solar heating. The concept is unusual and many are skeptical about its results, saying that the residents will get to comfortable in their so-called “transitional” homes and will not want to move to permanent housing, which may prove to be more expensive for them. The plan is set to take effect in January 2017 and end in five years in 2022. If proven successful, other cities in California may look towards San Jose for guidance.