The Real Power Behind South Korea: Chaebols

Avid fans can confirm that corrupt CEOs and other executives are often portrayed as antagonists of many Korean dramas.. When keeping in mind that fiction is branched from real-life events, would saying that the same concepts exist in present day South Korea be accurate?

In almost all of these dramas, the antagonists come from a chaebol family. Chaebol is a Korean word that refers to an industrial conglomerate that is run by a single person or family. Well-known examples include Samsung, Hyundai, LG, and KIA. These companies first sprouted in the 1960s and are still the center of controversy present-day.

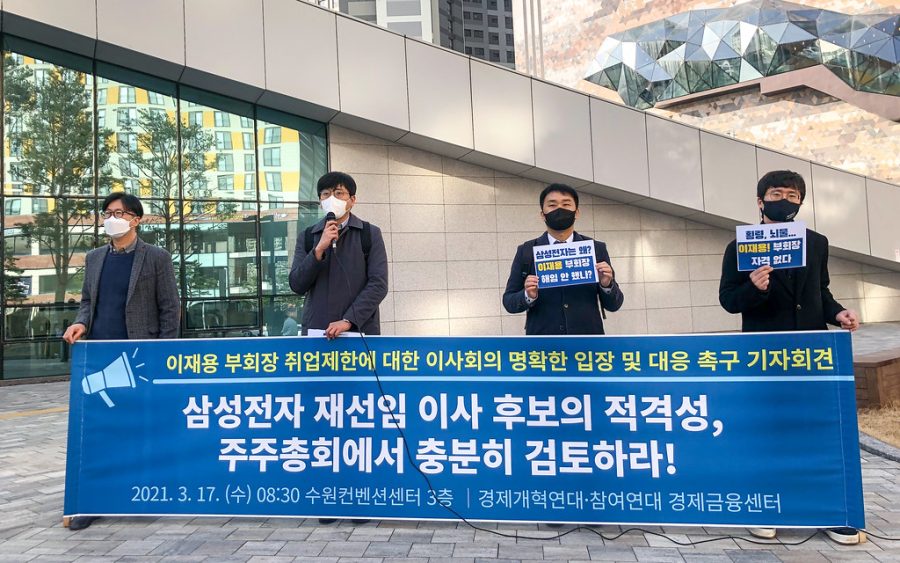

A well known case that exposed the behavior of chaebols was the “nut rage” incident relating to Heather Cho, the daughter of one of Korean Air’s major shareholders and the company’s vice president In 2014, she forced a Korean Air plane to change its flight route, causing delays and much more havoc; as if her actions couldn’t get more controversial, she even fired an employee because she was not pleased with the way they served nuts. Although the two parties initially planned to keep the incident quiet, the media’s dissemination of the news caused the public to immediately turn their backs on Cho. This led to her resignation from her position in the company and a prison sentence, which was later commuted after an appeal court. Still, this was a significant point in South Korean history. Sunsub Chung, a CEO of a news website, said, “There were many cases of Korean corporations and their abuse of power, but this was a very rare case where a member of the chaebol was actually prosecuted.”

However, such commuted sentences are not a new concept when it comes to chaebols. In fact, it happens so often that Hankyoreh Newspaper journalist Taewoo Park stated: “In the Korean judicial system there is the so-called ‘Chaebol Negotiation Rule.’ This is where [chaebols] are given a three-year sentence later reduced to a five-year probation.” Examples of this law negotiation include Chung Mong-Koo of Hyundai Motors, Cho Yangho of Korean Air, and Lee Kunhee of Samsung, who were all charged with tax evasion. Heather Cho also got a reduced verdict of 2 years probation from an initial eight months sentence.

Although most South Koreans are aware of how chaebols are able to slip through prison bars, residents of other countries may not be able to understand this “norm.” Taewoo Park continues his argument, stating that “the primary reason for letting them off with probation instead of jail time is the chaebols have contributed greatly to the country’s economy.”

This statement has been proven true time and time again, mainly with the most recent example of when South Korean president Yoon Suk-yeol pardoned a handful of chaebols from their prison sentences. Most significantly, Lee Jae-yong, the vice chairman of Samsung, and Shin Dong-bin, the chairman of Lotte Group, were pardoned. Both “successful” businessmen were sentenced for bribing former President Park Guen-hye. This pardoning received some backlash, but many agree that it was a decision that would help the country’s economy.

The existence and power of chaebols is an open secret among South Koreans, though the facts remain concealed for most foreigners. However, it is time to admit that South Korea is more than the rom-com K-dramas or the music it is known for. Perhaps there are hints and clues within the film it produces that exposes the country, only visible if fans look closely enough. Perhaps, like Albert Camus said, “fiction is the lie through which we tell the truth.”