American World History

George Santayana’s wise words “those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it” have resounded in the heads of many an educator. For all those with report cards on their refrigerators who think they have outsmarted this truth with an A+ in seventh grade World History, do not exempt yourself so quickly. Although many students have mastered history classes throughout their academic career, deeming them competent in the subject, our country has a terrible awareness of important topics such as foreign affairs. A National Geographic study discovered that only fourteen percent of Americans surveyed could find Iraq on a map, and Afghanistan came in at seventeen percent. So, how are students succeeding in school but failing to apply their knowledge to very real issues in the world today?

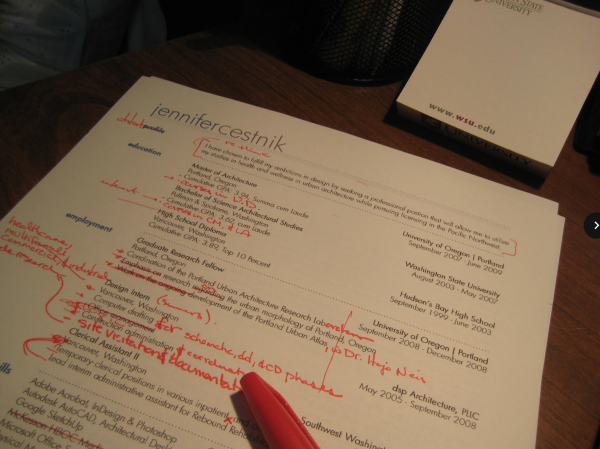

As many of you know, the two conventional options for incoming Wilcox tenth graders are World History and AP European History. I, myself, reflected on these choices during my freshman year, and regretted that our school did not offer an AP World History class. I understood that college-level courses often had to reduce the amount of material they covered to account for the depth that regular high school classes fail to achieve. However, no alternative class offered that same level of depth to African, Asian, or South American History. These classes may be offered in institutions of higher education, but high schools offering these subjects are certainly few and far between.

The current state standards for tenth grade World History boast “a truly global history,” yet the actuality of their worldliness does not live up to this optimistic language. In fact, the only time the state’s summation of the standards mentions a geographic location other than Europe or the United States is when it describes European trade with Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Additionally, California standards focus on movements such as the Enlightenment, the Scientific Revolution, and the Age of Reason, all of which originated in Europe.

While it would be ignorant to assume that our current standards omit non-European and non-American completely, a common theme resonates amongst the Asian, African, and South American societies that students do study. Students study African empires solely to describe their commercial contributions to the economies of European countries. In various classes throughout my academic career, we have crammed the histories of complex nations such as Japan or China into the span of a single chapter. And, of course, these rare chapters served as precursors to conflicts involving Europe or the United States. Even the Mayan, Incan, and Aztec Empires were only discussed briefly before students witnessed their demise at the rifles of the European man. Centuries of rich, complex history have all too often been compressed into mere fifty minute increments.

It is quite undeniable that when it comes to education and general awareness, entire continents become subordinate to Europe and the United States. This sad truth is no fault of our wonderful educators at Wilcox, whose passion for the social sciences is crippled by strict educational standards and standardized testing. But the innocence of our own educators ultimately does not overshadow what American ignorance is costing us in the long run. While nearly all Americans are aware of the conflict in Syria, few to none have been informed of the nation’s history and the complexities of their culture. Iran, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and more have been completely avoided in the American education system. And although the prolonged civil war in Africa is still a prevalent issue, the most prominent topic of foreign affair discussion is the Islamic State.

This system, designed to help young people construct a base of historical knowledge, skirts the real issues that students need to be informed about today. Maybe these topics are considered too dangerous to discuss, or maybe Americans are exclusively concerned with themselves. Either way, this self-interested culture when it comes to foreign affairs needs to end. If not, Santayana’s wisdom will certainly punish our fifty states–stuck in their revolving door of Eurocentric education and foreign affair policies.