Enduring the Somalian Refugee Crisis

With the threat of the world’s largest refugee camp’s closure looming, many Somali refugees are left to face a tough decision: head back home or wait to see if the camp officially closes. Dadaab, the world’s largest refugee camp, is on the verge of being shut down due to the fear of increasing terrorism, but the Kenyan High Court is working against the measure. Home to over 260,000 refugees, the fifty square kilometer camp provides a vital living place for thousands of people. The Kenyan government has been trying to shut Dadaab for years, but human rights groups and the High Court are opposing closure.

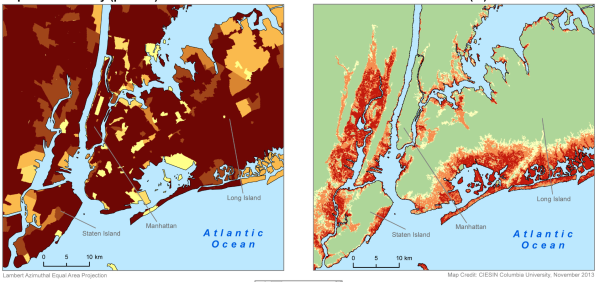

Dadaab was built as a sanctuary twenty five years ago for fleeing refugees, most of whom were escaping Somalia’s civil war. Located in Garissa County, Kenya, the camp’s five subcamps provide food, shelter, education, and healthcare to its inhabitants. The camp has been open since 1992, and was originally designed for 160,000 people, but the number has drastically increased due to famine and conflict in Somalia over the past few years. The camp was initially supposed to close on November 30th, 2016, but after being delayed and discussed in court, the Kenyan High Court (equivalent to America’s Federal District Court) repealed the notion.

According to a World Bank Report last year, Dadaab’s commercial services and activities such as shopping centers and kiosks help boost $14 million into Kenya’s economy annually. On the contrary, living conditions are scarce for many inhabitants—with meager food rations and flimsy shelters, refugees live tough lives. Furthermore, according to CNN News, the World Food Program’s funding has decreased, resulting in a thirty percent drop in food rations last year and leaving refugees with 33 percent fewer portions than the UN recommended amount.

Although Dadaab’s living conditions are poor and hunger runs high, to many, like Duh Ali Hanshi, having a safe place to live is enough. “I have children in school and I want them to continue with their education here, but right now we are living in fear,” says Hanshi, refugee of six years, in an interview with BBC. “We don’t know whether to go back to Somalia or to stay here. We will have to go back if we must go back.” Additionally, Halima Gure, owner of a popular Dadaab clothing shop, told The Washington Times that camp closure would cause many storeowners to lose business, not only impacting refugees, but camp workers, as well.

Despite the camp’s purpose of safety and protection, the Kenyan government fears refugees will be recruited to al-Shabaab, a nearby terrorist group. After Somali al-Shabaab members attacked the camp last year, killing 148 refugees, the government feared that the terrorists would use Dadaab as a base for recruitment. Eric Kiraithe, Government Spokesperson, released a press statement defending their actions, saying, “The camp had lost its humanitarian nature, and had become a haven for terrorism and other illegal activities. Our interest in this case, and in the closure of Dadaab Refugee Camp remains to protect the lives of Kenyans.” Although Dadaab is most likely not going to close after the recent ruling, hundreds of refugees have already chosen to return to Somalia.

Human rights groups such as the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights and Kituo Cha Sheria are opposing this decision. After human right organizations produced a petition deeming the act unconstitutional, the High Court came out with a ruling on February 9th. Judge John Mativo of Kenya’s High Court ruled that the government’s decisions were “specifically targeting Somali refugees is an act of group persecution, illegal, discriminatory and therefore unconstitutional,” successfully shutting down the notion.

The Kenyan High Court fears closing Dadaab will have serious negative impacts, especially amid an ongoing civil war and famine in Somalia. With the nation crumbling, Somalia has lacked an effective government for years, and its natural resources are scarce. In addition, according to UN agencies, 5 million Somalis already need humanitarian assistance, and closing Dadaab at the current state of Somalia will only add to that number.

“The closure of Dadaab is the decision that the refugees themselves will reach if and when they want to return,” said Mohamad Abdi Affey, the United Nations special envoy for Somali refugees, to BBC News. “If people want to come back to their country and need help, it is our mandate to help them, but we are not an advocate of return by any means.”

Kenya is amid a refugee crisis, and while the government wants to close the camp over the fear of terrorism arising, many humanitarians are calling closure unconstitutional, and that it is their responsibility to aid refugees. Whether closing the camp or keeping it open will be right decision, the lives of thousands of refugees depend on Kenya’s government and High Court.