They Have a Dream: Reflections on the Migrant Caravan

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

Rosalin Guillermo is just like your average mother. In her mid-thirties, she is a single parent and wants her five-year-old daughter and three-year-old son to “study and have a good future.” She worries that her phone will run out of battery before she gets a chance to charge it at the end of the day.

At 10:00 am on Sunday, October 21, Rosalin Guillermo clung to a rope that hung from a bridge. Below her churned the waters of the Suchiate River, which marks the border between Guatemala and Mexico. Several young men lowered her hand-over-hand to a raft that waited below, constructed of two inner-tubes tied together. As half a dozen people on the raft caught her and rowed to safety, a crowd of hundreds of watchers on the bridge cheered, “Si se puede!” Yes we can!

“Why did you do that?” a CNN reporter later asked Rosalin.

“To complete the dream that I had.”

Rosalin Guillermo and her two children are members of the migrant caravan that set out from Honduras in October. They walked from the town of San Pedro Sula through southern Guatemala until they reached the river, where they were stuck on the bridge for 24 hours as Mexican federales processed a few families at a time. Most of the refugees finally went back to the Guatemalan side and waited for an inner-tube ride across the river. A few intrepid travellers pried a hole in the fence and began lowering people, including Rosalin and her children, to the raft waiting below.

The caravan, which numbers between three and five thousand, communicates via Facebook and WhatsApp to stay on course, to circulate basic necessities like food and water, and to locate shelters (or failing that, basketball courts to sleep on).Traveling in a large group—and using social media to keep protective eyes on the caravan at all times—provides a degree of safety from cartels and human trafficking rings. But the reliance on social media poses unanticipated difficulties.

“To keep their phones charged is the most challenging thing at the moment, because they are traveling all the time,” says Ana Gabriela Rojas, BBC correspondent in Mexico. “Send a message, receive a message, and then continue […] Amazingly, the [network] companies from Guatemala, Mexico, and Honduras are all the same, so you have connection most of the time, 3G—but no electricity.”

The caravan is currently in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca, more than 1400 km from the Texas border where many members hope to request asylum. Their potential arrival weeks from now has ignited concerns in the US that asylum has become a backdoor for economic migrants.

The universal right to seek asylum is laid out in US law (the Refugee Act of 1980) and international law (beginning with the UN’s 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees).

Under this legislation, migrants have a right to seek asylum in a country of their choosing, a right to due process in that country, and “crucially, a right not to be sent back to a country where they will face persecution,” writes Abigail Stepnitz at the University of California, Berkeley. Whether their request is granted depends on the “credible fear interview,” in which an asylum officer assesses the credibility of the refugee’s fears for safety in their country of origin. Those who “pass” get a hearing before an immigration judge.

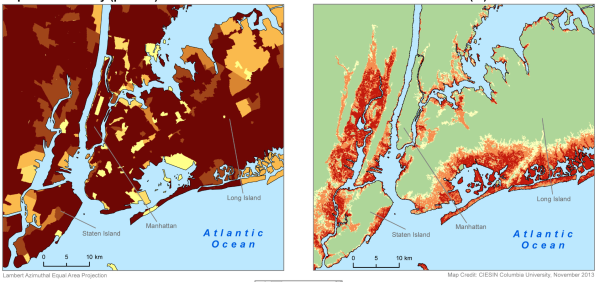

Last year, about 76% of asylum seekers passed the credible fear interview. But an analysis of six years of immigration court data by Syracuse University found that out of those who passed, immigration judges denied 75% to 90% of asylum seekers from Mexico, Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Haiti. China, meanwhile, only had a 20% rejection rate—even though it had the most applications by far. These data suggest a systematic pattern of discrimination against Latin American asylum seekers. What chances await the Honduran migrant caravan when, or if, it reaches the American border?

“We cannot educate, medicate, or incarcerate the whole world,” comments Texas Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick. In light of that astute observation, how do we balance compassion and human rights with the need to admit immigrants whose skills will strengthen our economy? And what do we say to immigrants who apply for work visas and green cards if we treat asylum seekers just the same? I don’t have the answers to these questions.

But there are other questions that matter, too. How will the United States, the country that turned away boatloads of Jewish refugees during World War II, grapple with its reputation of coldheartedness towards the refugees of the world? What can we learn from the rest of the developed world, which accepts far higher proportions of refugees than America ever has?

I wrote an alternate ending to the poem inscribed on the base of the Statue of Liberty. To the 2,300 children that UNICEF counted in the migrant caravan: Si se puede.

Here at our sunny southern gate you stand,

From hearth and home, a year if it was a day—

Exiles from a broken, bitter land

Who cling to cherished hope. What will we say?

“Take back your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

We have no room for the homeless anymore.”

Is it not our duty to redeem

The weathered promise of lady Liberty?

With lotteries and quotas do we not betray

The guiltless keepers of the migrant dream?