Nuke Scare

For many Americans, the far-off threat of North Korea’s nukes just got a lot more real. On January 6, 2016, the government-run Korean Central News Agency (KCNA) released a statement claiming that the country had detonated a hydrogen bomb—the most powerful weapon known to man. The alleged test corresponded to an earthquake that registered 5.1 on the Richter scale, according to the US Geological Survey.

When the news was released, the United States, South Korea, and Japan were among the first to condemn North Korea’s actions, which violated multiple international treaties and agreements regarding nuclear disarmament. The test was North Korea’s fourth and largest in the last ten years, following detonations in 2006, 2009, and 2013. International outrage has resulted as it becomes clear that Kim Jong-un, the leader of North Korea, has no intention of backing down and halting his nuclear development program, despite having incurred the harshest sanctions of any country on Earth. The North Korean government declared that their H-bomb was “capable of wiping out the whole US all at once,” dubbing America “the chieftain of aggression” and “a gang of cruel robbers.”

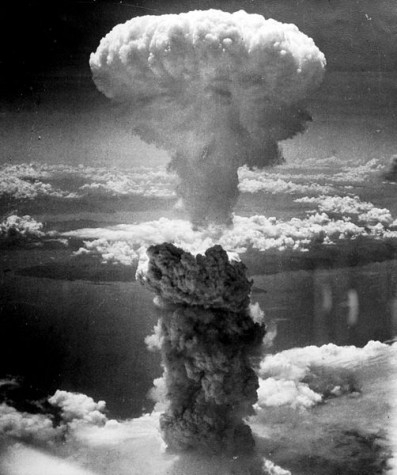

It is common knowledge that North Korea possesses nuclear weapons, but if they now have the materials and engineering to add hydrogen bombs to their arsenal, the world has reason to be alarmed. However, most experts have laughed at North Korea’s claim that they have tested a hydrogen weapon. Seismic readings of the blast indicate that the bomb measured less than six kilotons—barely a third the size of the nuclear bomb detonated by the US at Hiroshima in 1945. If it was truly a hydrogen device, the blast would have been roughly 10,000 times larger. In reality, it was most likely a very small-scale nuclear weapon, much like the ones discharged during the country’s three previous tests in the last decade.

The difference between nuclear and hydrogen weapons is in the method of detonation. Fission is the chemical process that splits molecules of plutonium or uranium to set off a radioactive chain reaction. Fusion, on the other hand, combines molecules to produce an exponentially greater amount of energy. A nuclear bomb uses fission only, while a hydrogen bomb uses fission to trigger a much larger fusion explosion. Because of this, hydrogen bombs cause devastation on a vastly larger scale. The atomic bomb dropped at Hiroshima near the end of World War II had a yield of fifteen kilotons, equivalent to 15,000 pounds of TNT. In comparison, the Tsar Bomba hydrogen bomb tested by the Soviet Union in 1961 had a yield of 50,000 kilotons—over 3,000 times larger.

The US and Japan convened an emergency meeting of the United Nations Security Council the day after the announcement. The goal of the closed-door meeting was to determine how the UN should respond, but no specific measures have been agreed upon yet. The Council is undoubtedly struggling to settle on a plausible course of action against “a country that for years has been impervious to international isolation and sanctions,” according to Anna Fifield of the Washington Post. These sanctions have included travel bans, trade embargoes, and the freezing of all of North Korea’s foreign assets. Even Russia has supported the strictures that the US has imposed on North Korea, a rare moment of unity during a time when the two countries are bitterly opposed over everything from Ukraine to Syria. However, China—North Korea’s closest ally—has been hesitant to cooperate.

Beijing certainly doesn’t like North Korea having nukes, but they don’t want to destabilize the country and end up with a surge of North Korean refugees from across the border. Even more importantly, China does not want North Korea to end up in South Korean, Japanese, or particularly American hands. “To some degree, China has opted to stick with ‘the devil you know’” rather than the one you don’t, says Fifield. Essentially, Beijing would rather put up with Kim Jong-un than risk having his regime collapse and one of China’s neighbors gain a strategic bulwark in the North Pacific. For this reason, China has turned a blind eye on Kim Jong-un’s nuclear program—and continued to trade busily with North Korea. At this point, with little options left for other countries to put the heat on Kim Jong-un, the pressure is on for China to use its economic influence over North Korea to end that nation’s nuclear aggression. The future of Kim Jong-un’s nuclear program, his dictatorship itself, and the security of the North Pacific—it all depends on China.